Infectious Diseases Case of the Month Case #39 |

|||

|

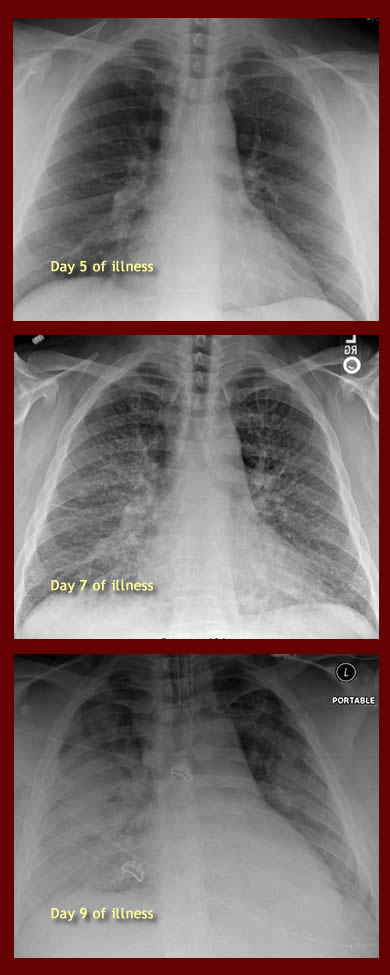

A 36 year old white male was admitted to the hospital in May 2012 with severe pneumonia. Although significantly overweight, he had otherwise been previously healthy and took no medications regularly. He had become ill about a week prior to admission with fever but no other localizing symptoms. He first sought medical attention on the fifth day of illness at which times fevers were reaching 1030 F and he had a slight sore throat. A CXR was normal (see Day 5 at left). He was prescribed amoxicillin. He was admitted to the hospital when he returned to the emergency room two days later, now suffering from a cough productive of pink sputum, fevers to 1040 F, and shortness of breath. Examination was notable primarily for his respiratory distress. There were no evident skin lesions. His CXR at that time is pictured at left (Day 7). Laboratory data included WBC 4.7, Hgb 13.8, Plts 56 (L). Oxygen saturation was 84% on room air. He was begun on IV ceftriaxone and azithromycin. He became rapidly and progressively more ill with increasing respiratory distress. On the third hospital day he was transferred to the ICU and intubated. His CXR showing diffuse bilateral infiltrates is shown at left (Day 9). Antibiotics were changed to piperacillin/tazobactam, levofloxacin, vancomycin, and oseltamivir. He experienced episodes of hypotension, and he developed renal failure. Nephrology consultants thought renal failure most likely was secondary to acute tubular necrosis based on review of urinary sediment and the various potential renal insults (hypotension, drugs, etc). His hypoxemia became so profound that he was placed in an apparatus to maintain him in a prone position to aid in his ventilation. Multiple blood cultures remained negative, and respiratory specimens were negative for respiratory viruses (PCR) and significant bacterial, fungal, or AFB findings (smears and cultures). A procalcitonin level was 0.98 (H). The patient lived in a rural region of Oregon's Willamette Valley and worked as a corrections officer. He had been absent from his normal work for the preceding three weeks as he attended his wife and their three week old newborn infant (neither wife nor infant had been ill). In addition to his work in corrections, he and his family harvested hay on their farm. During his absence from corrections work he had spent considerable time working on the hay harvest and in the hay barn. The family was aware of mice in the barn, but in general it was well ventilated. They also kept chickens, and the patient had recently cleaned the chicken coop as well as frequented an old trailer where the chicken feed was stored. Within that trailer while obtaining feed, the patient had recently been bitten by a mouse (through a thin leather glove). The family also had dogs and cats none of which had been ill or recently parturient. To further evaluate the patient's illness, a bronchoscopy was performed. The bronchoscopist noted the airways to be somewhat inflamed but to lack purulent secretions. Bronchioalveolar lavage fluid of a RUL bronchus appeared blood tinged. Bronchoscopic studies were non-diagnostic. Multiple serologies were ordered to further attempt to diagnose the cause of the patient's profound illness. |

||

What was the likely cause of this severe pneumonitis? |

|||

|

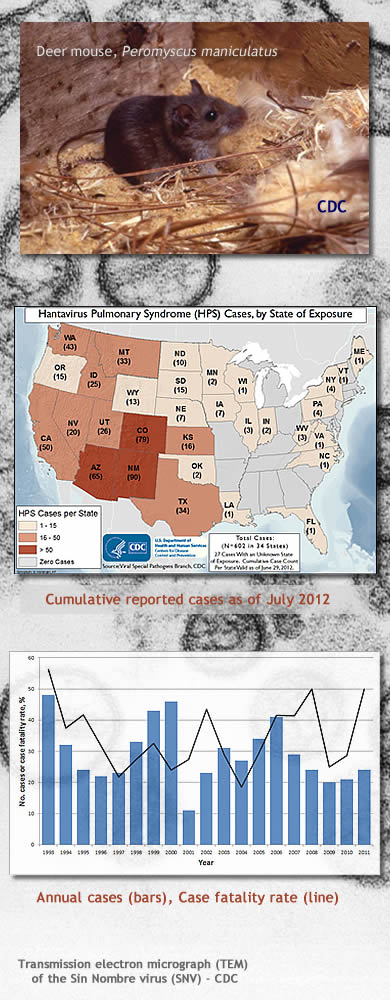

The patient had Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome (HPS) secondary to infection with Sin Nombre Virus. Diagnosis was made via serology (positive hantavirus IgM antibody) performed at a reference laboratory, subsequently confirmed by the Oregon State Public Health Laboratory. The result of this test became available on the ninth hospital day after the patient had already made substantial recovery from his respiratory failure. The patient's hospital course, as previously described, was characterized by rapid and profound respiratory failure with diffuse pulmonary infiltrates. With intensive care support his recovery from the severe respiratory failure was also relatively rapid such that he could be extubated on hospital day seven. Antimicrobials were sequentially discontinued. He was discharged from the hospital on hospital day eleven. His renal failure (creatinine had reached a maximum of 5.2) during his hospitalization eventually resolved. He did not require hemodialysis. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome has rarely been reported in Oregon, typically from drier regions of the state east of the Cascade Mountains. The syndrome was originally recognized in 1993 in the Four Corners region of the Southwestern United States when an outbreak of fulminant respiratory illness occurred. Investigation of the outbreak led to discovery of a previously unrecognized viral cause of severe respiratory illness in the U.S. The responsible hantavirus was originally named the Muerto Canyon Virus. Later the name was changed to Sin Nombre Virus in deference to sensibilities of the local residents of the Four Corners Region. Cases of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome have now (2012) been reported from 34 U.S. States (see map at left; Click here for a larger version). Sin Nombre Virus can be found in urine, feces, and saliva of infected deer mice, Peromyscus maniculatus. Other rodent species implicated in transmission of other strains of hantavirus to humans in the U.S. include the cotton rat, the rice rat, and the white footed mouse. Humans are infected primarily by respiratory exposure to aerosolized virus in excreta. Rodent bites can rarely transmit this infection as well and could have occurred in the case described. Illness begins as an undifferentiated febrile illness, a prodrome typically lasting 5-7 days before the abrupt development of profound respiratory illness. Clinical clues to possible hantavirus etiology of severe pneumonitis include thrombocytopenia, "left shift," hemoconcentration, and myocardial depression. Renal insufficiency can be present to a moderate degree but not usually to the degree seen in the case described. This may be in distinction to "old world" hantaviruses causes of Hemorrhagic Fever Renal Syndrome. Treatment of HPS is supportive. Case fatality rates remain high as illustrated by the graphic at lower left (larger version available by clicking here). The other choices in the preceding vignette (see original format) are causes of zoonotic illnesses. With the exception of illness due to Streptobacillus moniliformis all could cause severe respiratory illness. It would be difficult to distinguish between them on clinical criteria alone. The presence of an inoculation eschar could suggest tularemia and a bubo suggest plague (Case #19), but both of these diseases can occur in purely pneumonic forms. Infection with Streptococcus moniliformis, the cause of ratbite fever, most typically causes a syndrome of fever, rash, and migratory polyarthralgias. Ref: http://www.cdc.gov/hantavirus/ |

||

| Home Case of the Month ID Case Archive | Your Comments/Feedback | ||