Infectious Diseases Case of the Month Case #38 |

|||

|

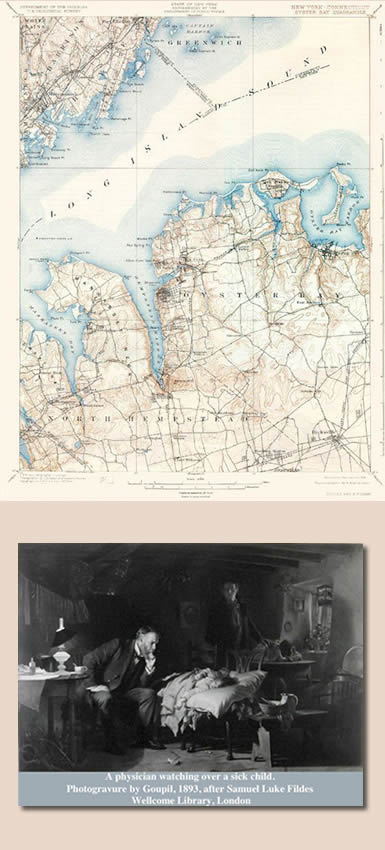

4th of July Special EditionAt the turn of the twentieth century Long Island was a popular summertime get away for wealthy New Yorkers, and Oyster Bay was a particular favorite (in fact, the summer White House was at the Sagamore Hill home of President Theodore Roosevelt near Oyster Bay). President of the Lincoln Bank and banker to the Vanderbilts, Charles Henry Warren was one such wealthy New Yorker, and he rented an Oyster Bay summer home from Mr. George Thompson in the summer of 1906. As befitting a family of such means, the Warren summer household also included a cook, servants, and a gardener. Unfortunately, the summer was to be anything but pleasant for the Warrens. In August a young daughter became severely ill with sickness characterized by high fevers, rash, and prostration. In short order five other members of the household developed similar illness including two maids, Mrs. Warren, the gardener, and another Warren daughter. Fortunately, despite the severity of illness and its prolonged nature, all eventually did recover. Physicians suspected a food or water borne illness, and a thorough investigation of household plumbing, possible shellfish poisoning, and possible milk contamination was conducted but was for naught. The citizens of Oyster Bay were very concerned about this outbreak of illness, but curiously, sickness remained confined to the occupants of the Thompson house. Such illness was very uncommon in affluent communities like Oyster Bay. In contrast, outbreaks of similar disease were distressingly common in the tenements of New York City, then the most densely populated places on earth. Mr. Thompson, the owner of the house, was concerned that unless he discovered the root of the problem that led to the Warrens' illnesses, he may be unable to find tenants for his property in subsequent summers. Therefore, he went to the unusual step of hiring a civil engineer steeped in the new field of bacteriology to further investigate. At first this investigation likewise yielded no clue. However, eventually his queries led someone to recall that there had been another summertime household member, a cook who had left employment in early August before the disease outbreak. The whereabouts of this cook were not immediately known. Although the employment agency that had arranged her employment by the Warrens did not know where she was, the investigator did learn from this source of other well-to-do families that had employed the same cook. To his amazement, he learned that over the preceding ten years six of eight families where this cook had been employed had suffered similar outbreaks of severe, prolonged febrile illness. Eventually the cook was located. Who was she? |

||

Who was the cook? |

|||

|

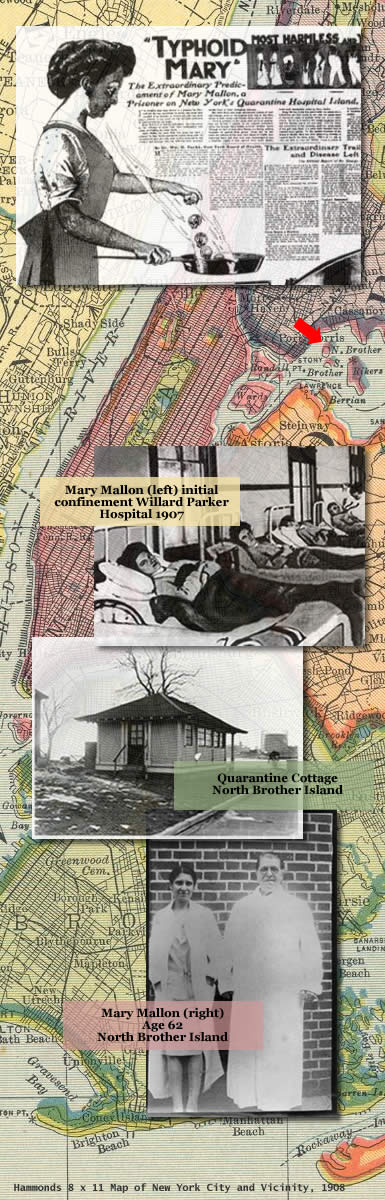

The cook was Mary Mallon, a chronic carrier of Salmonella typhi. At the beginning of the twentieth century typhoid fever was a common illness, and in New York City alone there occurred an estimated 4,000 new cases per year with a 10% mortality. At the time the cases of typhoid fever in the Warren family were investigated, the concept of asymptomatic carriage had only been described in the medical literature by Robert Koch four years previously. Charles Soper, the civil engineer with an interest in typhoid fever (he had worked to understand and contain previous outbreaks of this disease), was aware of this new concept of asymptomatic carriage. When he initially approached Mrs Mallon, a thirty seven year Irish immigrant, with his suspicion about her roles in the several outbreaks of typhoid fever, she at first was completely uncooperative and refused to believe that a healthy individual such as herself could have had any role in transmission of disease. Ultimately, NYC public health authorities apprehended her. After her stools were proven to indeed be positive for Salmonella typhi, she was placed in the city's quarantine hospital (Riverside Hospital) on the city's quarantine island (North Brother Island in the East River). Her internment was performed with little that could be considered due process either by contemporary or certainly by modern standards. Mary Mallon protested her confinement to North Brother Island with great vehemence in letters to public health authorities and others, and her cause was featured by William Randolph Hearst's New York American newspaper. It was there that her identity was revealed and the appellation Typhoid Mary appeared (it was rumored that Hearst even funded Mary's appeals for release in order to sell papers!). After three years of confinement on North Brother Island Mary was finally released in 1910 after a new (and apparently more sympathetic) NY Public Health Commissioner agreed to do so under the conditions that she would report regularly and not work as a cook. By that time it had become known that 1-3% of all persons infected with Salmonella typhi became chronic carriers. This was an enormous number, and it was apparent that not all could be confined as was Miss Mallon nor should they be - with the exception of those who worked in food preparation they generally posed little public health threat. In 1914 Mary Mallon vanished from the eyes of the NYC Public Health department. In March 1915 there was an outbreak of typhoid fever at the prestigious Sloane Maternity Hospital in New York City where 25 persons became ill and 2 died. Charles Soper was once again enlisted to investigate. When shown a handwriting sample of Mary "Brown," a hospital cook, Soper was amazed to see that it was unmistakably that of Mary Mallon! Once again she had chosen to work as a cook and again was responsible for an outbreak of typhoid fever! Mary was returned again to quarantine on North Brother Island (this time with little protest). Although she eventually was allowed to visit New York City for brief visits (and eventually befriended and worked with doctors and nurses at Riverside Hospital), she remained quarantined on the island for the next twenty-three years - until she died in 1938! The other choices offered in the preceding vignette (see original format) are all famous women of American history. Mary Todd Lincoln (the former Mary Ann Todd) experienced the tragic loss of her young son, Willie, to typhoid fever in 1862. Mildred Elizabeth Gillars was infamously known as Axis Sally during World War II in her role as a Nazi propagandist. Martha Jane Canary a.k.a. Calamity Jane was a colorful character who made claim on relationships (often a bit dubiously) with several famous romantic figures of the American "Wild West." Finally, Catherine O'Leary's cow probably didn't kick over the lantern that started the Great Chicago Fire, but it made for great press (and the fire actually probably did start in her barn!). We can only hope that public health quarantine may now be more enlightened (or at least less lengthy!) should we be the next unfortunate "Typhoid Marys." We must also be grateful, nonetheless, that typhoid fever is now a rare disease in the United States thanks to the efforts of public health. Happy Fourth of July! Ref: Nova - Typhoid Mary: The Most Dangerous Woman in America (DVD, 2005) |

||

| Home Case of the Month ID Case Archive | Your Comments/Feedback | ||