Infectious Diseases Case of the Month Case #31 |

|||

|

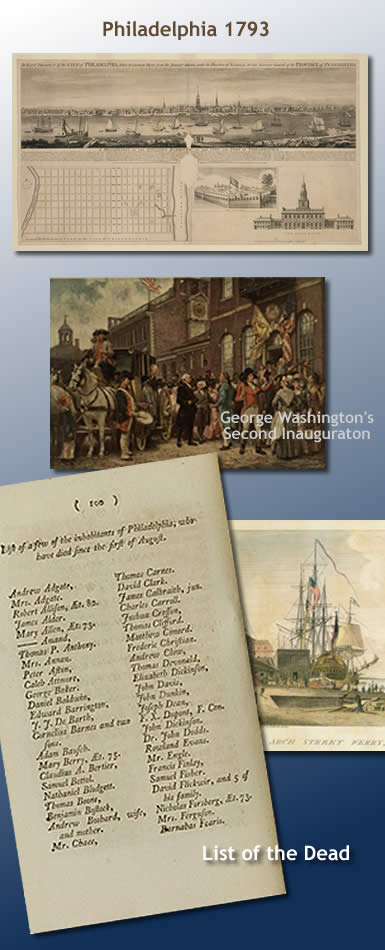

4th of July Special EditionIn 1793 Philadelphia was the largest city in the United States with a population of 51,000 and it was the country's temporary capital. George Washington was reinaugurated for his second term as President in March. Each action of the government of the fledgling nation was fraught with the precedent it might establish. In foreign policy there was preoccupation with the activities of France whose own revolution was considered by many as the logical continuation of the American Revolution. The excesses of the French Revolution and the relative weakness of the new American state persuaded President Washington to avoid entanglement in European affairs involving France. This was much to the dismay of many including prominent members of his own administration. The arrival in July of 2100 French refugees from the slave rebellion in Santo Domingo only aggravated the tensions. The summer of 1793 had been one of unrelenting heat and humidity. Sanitary measures in the city were essentially nonexistent - open sewers were particularly "ripe", and residents were apt to add to the noxious "soup" by tossing dead animals into the deep holes into which these sewers drained. To add to this in August was the stench of rotting coffee dumped on the Delaware River wharves after it had arrived spoiled from Santo Domingo. The eighty odd physicians of the city had witnessed a series of infectious diseases that year - mumps in January, jaw and mouth infections in February, scarlet fever in March, and influenza in July. In August they began to see the onset of an even more virulent febrile illness. This illness began with high fever and chills, headache, and a painful aching in the back, arms, and legs. These signs and symptoms lasted for about three days before patients appeared to temporarily improve only to relapse with high fever and the development of jaundice, bleeding of the gums, and black stale vomitus. Prostration and delirium presaged the death of patients which began to occur at an alarming pace. Initial cases appeared to cluster near the Delaware River wharves. Word of the epidemic spread. The mayor placed a notice in the newspaper that there was "great reason to apprehend that a dangerous infectious disorder" was loose in the city. Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and one of the country's most respected physicians, advised his friends to flee the city. Soon a mass panic and exodus of the residents of Philadelphia was in progress. When Secretary of Treasury Alexander Hamilton experienced a mild case of this illness, this exodus came to include many members of the Washington administration including Hamilton, Secretary of State Jefferson, and even George Washington himself (causing an early "constitutional crisis"). Physicians were uncertain as to the cause of this illness. Among the various possible causes were suggested jail fever, camp fever, military fever, and autumnal fever. For those physicians that remained in the city there was little to do for the victims to whom they ministered. Benjamin Rush administered a harsh regimen of bleeding and purgatives though other physicians strongly disputed this practice. When many of those who had the means had fled the city, the city became relatively deserted and quiet. Unfortunately, not all could flee, and illness and death continued. Paradoxically, the city also became a much cleaner place as a leading theory of the cause of this illness was that the unsanitary nature of urban life contributed to the development of the epidemic, and efforts were made to clean up the filth. Finally, as mysteriously as the illnesses had begun, the epidemic ebbed with the advent of cooler weather in the fall. Residents returned to the city but only after roughly five thousand (one tenth of the population) had succumbed to this fever. |

||

What was the likely vector of this lethal febrile illness? |

|||

|

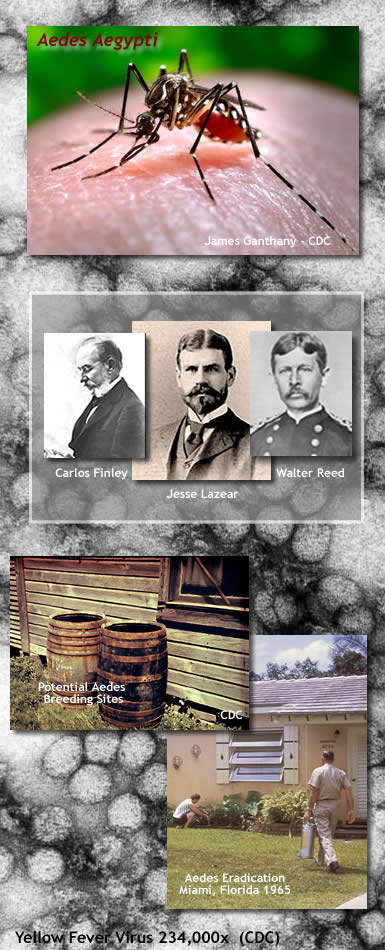

This lethal epidemic of febrile disease was due to yellow fever likely transmitted by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Yellow fever is caused by a flavivirus transmitted to humans by mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti in "urban" yellow fever). After an incubation of 3-6 days illness begins and may range from asymptomatic infection, to undifferentiated "flu-like" illness, to severe hemorrhagic fever with mortality rates of up to 50%. As was described in the vignette, those patients who experience hemorrhagic fever may do so after a brief interlude of improvement before entering a more profound period of illness with jaundice, diffuse hemorrhage, acidosis, CNS dysfunction, shock and death. As in 1793 there remains no specific therapy for yellow fever.Yellow fever is believed to have originated in Africa although the first recognized outbreak occurred in the New World in 1648. Presumably yellow fever arrived in the New World via the African slave trade. To their credit Benjamin Rush and his colleagues recognized the illness in 1793 as likely yellow fever having been aware of or having witnessed prior outbreaks of this illness. Yellow fever indeed was no stranger to 17th through 19th century North America. Epidemics could be terrifying and be associated with high mortality with whole cities emptying in panic (See Yellow fever in the United States). An interesting historical aside, extraordinarily high yellow fever mortality experienced by French forces in Hispaniola indirectly led to the U.S. acquiring the Louisiana territory when it helped persuade Napoleon to curtail his designs on the New World. That yellow fever might be transmitted by mosquitoes was initially an idea treated with skepticism if not ridicule. Carlos Finley, a Cuban physician, was an initial proponent of this idea and went to the extraordinary step of identifying and mapping species of mosquitoes whose occurrence appeared to coincide with outbreaks of yellow fever disease. The Spanish American War gave urgency to the United States Army to find means of combating this disease which caused many more casualties than did actual combat. Jesse Lazear, an army scientist, inadvertently (or purposely) exposed himself to potentially infected mosquitoes in the course of attempting to demonstrate mosquito transmission. When he sickened and tragically died of yellow fever, Major Walter Reed, an initial skeptic of the mosquito transmission theory, embarked on formal controlled human experimentation which convincingly demonstrated that mosquitoes were the disease vector. When epidemics of disease in Cuba greatly diminished or ceased as a consequence of mosquito eradication efforts, the idea of mosquito transmission was conclusively established. By eradicating breeding sites or mosquitoes themselves (see photos at left) yellow fever was eliminated as a threat from many areas where it previously was endemic/epidemic. This public health triumph allowed, among other things, the successful construction of the Panama Canal. Earlier efforts at canal construction across the Isthmus of Panama had been thwarted by this disease and malaria. A vaccine was developed in the 1930's whose successor remains in use today. Yellow fever risk today is confined to areas of Africa and South America. The other items listed in the preceding vignette can also be vectors of infectious disease. Ixodes scapularis, the deer tick, is a vector of lyme disease, anaplasmosis, and babesiosis. is a mosquito vector of malaria, a problem in the U.S. until the 20th century. Xenopsylla cheopis is the flea vector of plague. Finally, Delaware river water was likely quite unsanitary and could have been a source of typhoid fever, cholera, or other waterborne illness. Happy Fourth of July - don't forget the DEET! Ref: Murphy, J., An American Plague, The True and Terrifying Story of the Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1793, Scholastic Press, 2006. |

||

| Home Case of the Month ID Case Archive | Your Comments/Feedback | ||